We are often asked by users of MoveIt how to plan Cartesian motions for robotic manipulators. Such motions are useful for many applications that require the end effector or tool to follow an exact path along a surface, such as seen in welding and painting applications. Another application ideally suited for Cartesian planning are closed-loop, real-time applications that require very reactive behaviors from the robot, such as teleoperation.

Cartesian planners have historically not included the ability to avoid collisions, and instead assumed the workspace was relatively free of obstacles. This assumption works in many applications, but as demands for robotics continue to increase, the blending of Cartesian planners with another class of planning, global motion planning, is needed.

Recently, MoveIt’s Cartesian planning capabilities have improved on several fronts, enabling better performance for real-time Cartesian planning and new capabilities for global, collision-aware Cartesian planning. This whitepaper will discuss desirable properties for Cartesian planners in general and use them to classify the different Cartesian planning options available within MoveIt. This will enable you to choose the Cartesian planning features in MoveIt that are right for your application.

Background

In the context of robotic arms, Cartesian planning is the generation of motion trajectories where a goal is specified in terms of the desired location of the end effector. This is in contrast to joint-space planning, where a goal is specified as exact joint positions such as joint 1 equals 90 degrees, joint 2 equals 45 degrees, etc. A Cartesian goal is a six degree of freedom pose, which typically fully specifies the position and orientation of the end effector or tool (although it is not uncommon to only partially constrain the end effector pose).

Cartesian planning often supports various types of constraints that a global joint-based planner does not. One example of Cartesian constraints is keeping the robot’s end effector upright so as to not spill a glass of water it is holding. Other examples include: tracing a welding path (with tight constraints on position, and slightly more relaxed constraints on orientation) or keeping an object within the field of view of an end-of-arm-mounted camera.

Desirable Properties of Cartesian Planners

Completeness

Completeness is a property that indicates the motion planner will find a solution to the planning problem if one exists. Many global motion planners are either probabilistically complete (e.g. PRM or RRTConnect) or resolution complete (e.g. A* or D* Lite). Jacobian-based Cartesian planners, in contrast, are typically not complete. Such planners may sometimes indicate that a desired pose cannot be reached even if a solution does exist. This is because they do not have good recovery mechanisms and can easily get stuck in local minima. Examples of local minima include joint limits and singularities.

Underconstrained

Some Cartesian planners do not require that the pose be fully specified; these are called under-constrained motion planners. Planners with this property are useful for applications like holding a marker where, for example, you may not care about the orientation of the symmetrical object in your hand or the exact angle of the tip of the marker against a surface. Any tool that has a tip that is flexible in its usage orientation is a good candidate for an underconstrained planner. One of the big advantages of not fully defining the pose of the task is that the workspace is greatly increased, allowing for smaller robots with possibly fewer degrees of freedom to still accomplish difficult tasks.

Planning Ahead

The ability for a Cartesian planner to plan ahead has a lot of benefits such as the ability to decelerate before hitting an obstacle. Other use cases are material removal or additive applications such as painting or blending, where you want to ensure the entire surface of an object is adequately covered. However, the ability to plan ahead often conflicts with realtime requirements for the planner. The more future calculations are required, the less reactive and real-time the Cartesian planner becomes (discussed next).

Realtime

The term realtime is often misused or is ambiguous, but for our purposes it means what kind of timing guarantees the planner provides such that it can reliably hit a certain control frequency, such as 100 hz. Global motion planners are notoriously bad at providing real-time guarantees. This is due to the fundamental complexity of motion planning; better algorithms will not change this. There is a distinct tradeoff between completeness and real-time capabilities. However, there are many important robotics applications where real-time guarantees are necessary, such as robotic surgery, teleoperation, or dynamic operations like picking from a moving conveyor belt.

Dual Arm or Whole Body

Most robotic arm applications today focus on the problem of controlling a single arm; dual arm applications are still on the fringe of commercially viable robotic solutions. However there is a growing need for dual arm Cartesian control which requires extra computation to ensure the robot arms do not collide with each other. Whole body Cartesian planning is the step beyond that, incorporating control of a torso, legs, or wheels such as found on most humanoid robots.

Human-Like Motions

This is a common request PickNik hears from our clients: the elusive quality of “human like’’ behavior. This is typically described as arm motions that keep the elbow pointed down, the default behavior of humans as it minimizes energy. Above is an example of a human in an awkward position with elbows up. However, this position is halfway through an optimal motion movement for humans. It is the Olympic lift called a snatch. In Cartesian planning, the request for human-like motions can often be achieved by adding extra constraints to the Jacobian matrices in the form of weights that bias behavior.

Available Planners

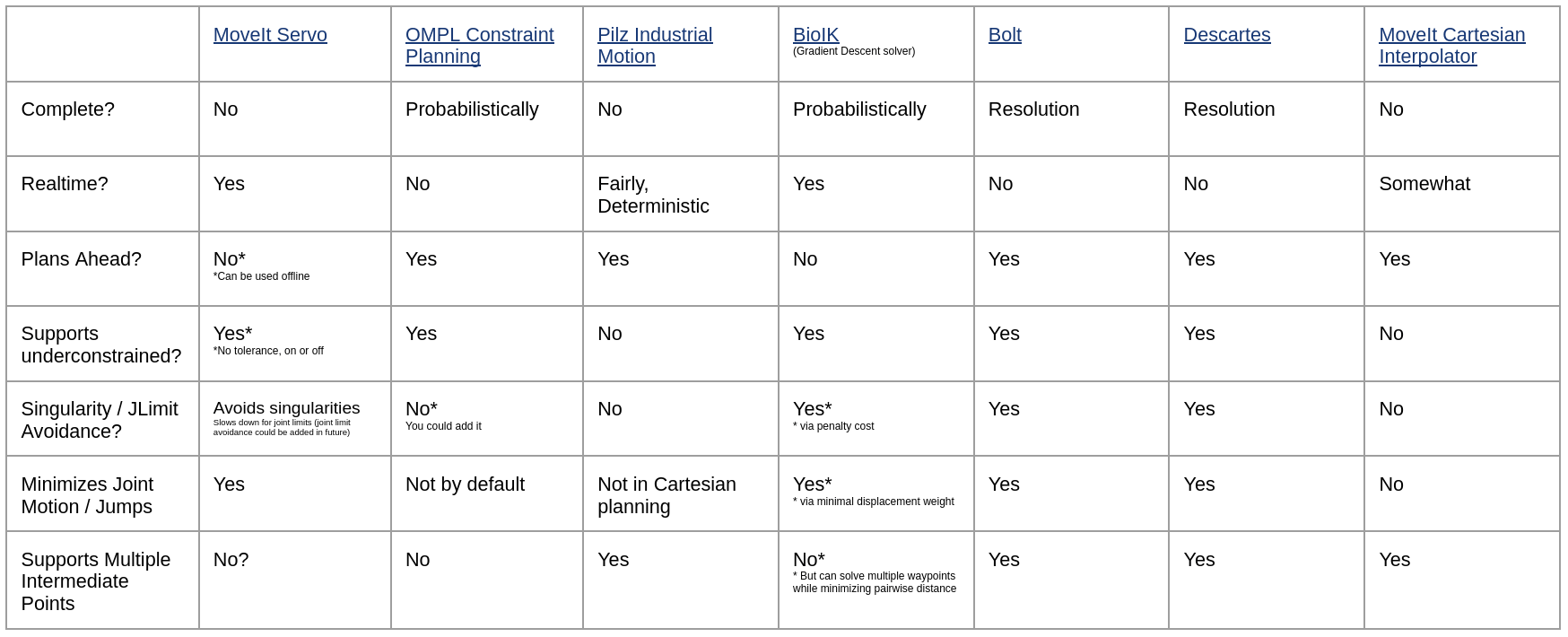

The MoveIt global community, in collaboration with PickNik Robotics, has been moving towards much better Cartesian planning functionality than MoveIt’s original focus of OMPL-style global planning. As of this writing there are at least 7 approaches to Cartesian planning available with MoveIt. These options can be overwhelming, as no one approach is best for every use case. Instead, the right tool must be selected for the right application. This section outlines some of the pros and cons of each planner, with a summary in the following table:

MoveIt Servo

Servo is the recommended realtime Cartesian planner in MoveIt, ideal for teleoperation and visual servoing. Originally developed at UT Austin, Servo’s approach has been extensively upgraded and integrated into MoveIt over the past few years. It uses Jacobian-based solvers and avoids collision with its environment.

OMPL Constraint Planning

The recently added constraint planning functionality in MoveIt are cutting edge and in active development. This approach uses random sampling and projection methods to ensure plans obey constraints, including Cartesian constraints. Full tutorials.

Pilz Industrial Motion

Traditional point to point Cartesian motion planners are now available from collaborators at Pilz GmbH. These planners are useful for mimicking the behavior in industrial robotic arms and are deterministic.

BioIK

BioIK is a particle optimization & generic inverse kinematics algorithm that searches for a valid robot joint configuration while optimizing for multiple goals and local minima. It’s particularly suited for whole body control and at finding approximate solutions for very challenging problems. BioIK has been developed by the TAMS Group. Full tutorials.

Descartes

Descartes performs brute-force path planning on under-defined Cartesian trajectories. It takes as input a multi-point reference tool path and discretizes the path into a searchable tree, and then generates a joint trajectory that complies with the constraints of a given process. Descartes was developed by the ROS Industrial Consortium. Full tutorials.

Bolt

Similar to Descartes, Bolt uses a discretization approach to search over a tree that solves the Cartesian planning request. Bolt supports dual arm manipulation and can be integrated with probabilistic roadmaps for multi-modal planning problems. Bolt is an in-development product of PickNik Robotics that combines Cartesian capabilities with experience-based planning: it bootstraps planning for new motion planning problems with solutions computed previously for similar problems It does so while still preserving strong guarantees on completeness and optimality.

MoveIt Cartesian Interpolator

For historical reasons, the MoveIt MoveGroup interface exposes a computeCartesianPath() API that uses the default Cartesian Interpolator functionality in MoveIt. This Cartesian planner is greedy and easily gets stuck in local minima as it does not provide any functionality for avoiding joint limits or restarting. While as of this writing this is still the default behavior, we recommend avoiding this Cartesian planner.

Future MoveIt Roadmap

PickNik and the MoveIt Community will continue to improve the Cartesian functionality available in MoveIt. PickNik’s current focus is on MoveIt Servo and the OMPL Constraint planning functionality, though there has been recent interest in further integrating BioIK. One particular pain point is changing the default API in MoveIt 2 to no longer use the original Cartesian Interpolator. Everyone is encouraged to become contributors to the open source MoveIt project and improve Cartesian functionality in MoveIt.

Conclusion

There are many competing requirements when evaluating which Cartesian planner to use for your application. The primary properties to consider are completeness, support for under-constrained reference paths, the ability to plan ahead, realtime requirements, dual arm control, whole body control, and finally the characteristics of human-like motions. While the theory behind these algorithms gets very academic, we hope this whitepaper provides a high level review of which planners provide which properties, as well as more subjective criteria such as development status.

For further information, do not hesitate to reach out to PickNik Robotics, the leading maintainers of the MoveIt project. PickNik is available for further development, integration, and training for Cartesian robotic arm planning.